COUNCIL REPORT III/IV -- APRIL 2003

Learning from Traditional Mediterranean Codes

Note: This essay appears in the "Council Report

III/IV," which contains a wealth of additional material on urban

design, architectural style and codes. Click

here for more information, or download the order

form.

The mindset and associated skills of the contemporary

architect whose ideology is rooted in modernism and post-modernism does

not provide her or him with the outlook and skills necessary to intervene

intelligently in habitat. Developers and homebuilders have taken the role

of habitat producers, driven by the notion that habitat is a product to

be manufactured and sold like any other product in the marketplace, without

concern for livability or the quality of neighborhoods. Yet for a successful

habitat to emerge, we need to learn from the experience of previous eras

and cultures that managed to produce habitats and neighborhoods superior

to those produced since World War II in the United States. The generative

system and related processes of decision-making and the nature of the

control mechanism used, particularly the system of codes and their application,

is paramount to understand and learn from if we are to intelligently intervene

in the processes that generate and produce great places to live. This

short essay attempts to point out the main features of traditional codes

in various regions of the Mediterranean.

|

|

The essence of the traditional system prevalent in the

Mediterranean region is found in the ethics and values related to habitat.

Based on textual and built evidence, this is a system that has its roots

in ancient Near East civilizations.

A primary element is respect for one's local traditions and customs. This

translates to values that perpetuate a local typology. Mediterranean practice

borrows from local typology when undertaking a new building project and

may improve on certain aspects related to construction and architectural

details. The master builder may exercise his own improvements on what

is an established local design language. The idea that a building is designed

with a totally foreign design vocabulary is unthinkable. It would be viewed

and considered an act of arrogance, which religious values condemn.

A second major element is the importance attached to good relations with

immediate neighbors, and with others in the neighborhood that fosters

a sense of community. Such good relations, based on trust, mutual respect

and peace, translate into ethical codes guiding construction that affects

proximate neighbors.

A third major element is the cleanliness and maintenance of the immediate

public realm, primarily streets and cul-de-sacs. These spaces are the

responsibility of the owners or tenants of adjacent buildings whose external

walls abut the public realm. The concept of the fina (Arabic word),

an area of about 1.0 to 1.5 meters in width (3 feet, 3 inches to 5 feet)

alongside the external wall(s) of a building abutting streets and access

paths, was understood to convey certain rights of temporary usage to the

owner or tenant of the abutting building, along with responsibilities

for cleaning, maintenance, and insuring the removal of any impediments

to the public right of way, such as removal of rainwater accumulation,

mud and snow.

Two sources are used. The first is from Byzantine culture in Palestine,

the treatise of Julian of Ascalon, dated 533 A.D., early sixth century.

The second is from Islamic culture in Spain, the treatise of Ibn al-Imam

(died 996 A.D.), dating from the late 10th century.

The goal and intentions of Julian's and Ibn al-Imam's treatises are as

follows:

The goal is to deal with change in the built environment by ensuring that

minimum damage occurs to preexisting structures and their owners, through

stipulating fairness in the distribution of rights and responsibilities

among various parties, particularly those who are proximate to each other.

This ultimately will ensure the equitable equilibrium of the built environment

during the process of change and growth.

Assumed intentions of Julian's and Ibn al-Imam's treatises:

1. Change in the built environment should be accepted as a natural and

healthy phenomenon. In the face of ongoing change, it is necessary to

maintain an equitable equilibrium in the built environment.

2. Change, particularly that occurring among proximate neighbors, creates

potential for damages to existing dwellings and other uses. Therefore,

certain measures are necessary to prevent changes or uses that would:

i) debase the social and economic integrity of adjacent or nearby properties,

ii) create conditions adversely affecting the moral integrity of the neighbors,

and iii) destabilize peace and tranquility between neighbors.

3. In principle, property owners have the freedom to do what they please

on their own property. Most uses are allowed, particularly those necessary

for livelihood. Nevertheless, the freedom to act within one's property

is constrained by preexisting conditions of neighboring properties, neighbors'

rights of servitude, and other rights associated with ownership for certain

periods of time.

4. The compact built environment of ancient towns necessitates interdependence

among citizens, principally among proximate neighbors. As a consequence

of interdependence, it becomes necessary to allocate responsibilities

among such neighbors, particularly with respect to legal and economic

issues.

5. The public realm must not be subjected to damages that result from

activities or waste originating in the private realm.

Specific issues addressed by Julian's treatise are land use, including

baths, artisan workshops, and socially offensive residential uses; views,

for enjoyment and those considered a nuisance; drainage and planting.

In the case of houses and condominiums, the treatise addresses acts that

debase the value of adjacent properties, walls between neighbors, construction

details, and condominiums in multi-story buildings and those contiguous

with porticos.

Ibn al-Imam had another important intention articulated in his treatise:

It is the right of a neighbor to abut a neighboring existing structure,

but he must respect its boundaries and its owner's property rights.

Specific issues addressed by Ibn al-Imam's treatise are land use, including

mosques, bakeries, shops and public baths; streets, including open-ended

streets, cul-de-sacs, "fina," projections on streets, servitude and access;

walls, including abutting and sharing rights, and ownership rights and

responsibilities; overlooking, including visual corridors that compromise

privacy; drainage and hygiene, including responsibilities for cleaning

toilet septic tanks and removal of garbage; planting and animals.

Pyrgi, village on the island of Chios, Greece, whose origins date back to the mid-14th century. The air photo is of the northern half of the village, taken in 1934. Courtesy of Ministry of Public Works, Aerial Photos Department, Greece. |

There are a number of codes related to the issues covered

by Julian and Ibn al-Imam. I have selected four codes that tended to be

universal in their impact in shaping the built form of traditional towns

in the Mediterranean. Local customary practice determined the final form

and character of a place.

PARTY WALLS: Buildings abutting each other on more than one side were

a major feature of ancient and traditional towns dating back to 2000 B.C.

and earlier in the Near East. Julian recognized this age-old custom in

Palestinian towns and addressed it in his treatise. The longevity of this

custom in the Byzantine and post-Byzantine periods can be traced, over

1,200 years, to a ruling in 1777 in documents found at the island of Syros

in the Aegean. In Islamic culture the issue of sharing party walls was

affirmed by the Prophet himself during his reign in Medina (622-632 A.D.),

which translates as: "A neighbor should not forbid his neighbor to insert

wooden beams in his wall." This saying is always quoted by Muslim jurists,

including Ibn al-Imam and others who wrote about construction and design

codes, to ensure that neighbors respect this right. Implementation details

for this stipulation were developed by jurists and are fully documented

in Islamic jurisprudence literature. The air photo of a traditional town

in Greece demonstrates the impact of this stipulation.

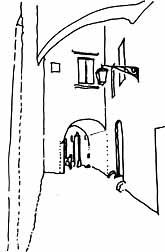

FINA (SYN: HARIM): This is an invisible space about 1.0 to 1.5

meters wide alongside all exterior walls of a building that is not attached

to other walls, and primarily alongside streets and access paths. It extends

vertically alongside the walls of the building. The owner or tenant of

the building has certain rights and responsibilities associated with his

fina. Although Julian does not specifically mention it, its usage is clearly

evident in Greek towns and villages that have survived since the post-Byzantine

period, primarily from the post-1500s period. There is adequate evidence

for this concept from pre-Islamic history in Arabia; the concept was thoroughly

recognized by Muslim jurists and scholars in the extant literature of

the Near East, North Africa, and pre-1500 Spain.

A street in Ostuni, Puglia region, Italy. Note the projecting lamp is high enough for traffic below, and is within the fina of the house. The sabat belongs to the house on the right. The arch spanning the street is built to reinforce the stability of the walls, implemented after agreement between owners of the facing houses. Sketch by author after a photo in "Italian Hilltowns" by Norman F. Carver Jr. |

It is a powerful concept and an effective tool that

has done much to allow the articulation of the facades and thresholds

along the public realm. Built-in benches near entrances, troughs for vegetation,

high-level projections in the form of balconies and enclosed bay windows,

and rooms bridging the public-right-of-way (sabat -- Arabic term

-- discussed below) were all possible due to implementing the various

allowances of this concept. Maintenance of streets and private passageways,

by keeping them clean and safe from obstructions, was also related to

the responsibilities associated with using the fina.

VISUAL CORRIDORS: Views -- from primary windows, balconies and terraces

of houses -- of the sea, mountains, gardens and orchards were considered

important in Byzantine and later Greek culture. Accordingly, stipulations

and codes were devised to protect these assets. Evidence of such codes

exists since the Roman period and from the late 5th century Constantinople.

In Islamic culture, protection from visual intrusion into the private

realm of houses was the paramount consideration. Views were appreciated

when available, but they took second place to the blocking of visual corridors

into the private realm. Roof terraces in many traditional towns in the

Muslim world would be screened by parapets to discourage overlooking neighboring

terraces. Bay windows towards the public realm, usually located at upper

levels, would be screened by wooden lattices that allowed views of the

outside but prevented those outside from seeing in.

SABAT (SYN.: STEGASTO [NAXOS] AND KATASTEGIA [MYKONOS] ): The configuration

and possibility of bridging the public right-of-way emanates from the

concept of the fina. It is a device that allows the creation of

additional space attached to a building. Codes written by Muslim jurists

clearly stipulate the legal rights associated with constructing sabats.

A street in old Tunis, Tunisia. Note the steps for the house on the right are within the fina. Windows are above eye level and above the sabats. Photo taken by author in the mid-1970s. |

When buildings on both sides of a street are owned

by the same person, he can create a sabat by directly using the

walls for support. When somebody else owns the building on the opposite

side of the street, then the party who wants to build a sabat might

opt to use columns for support abutting the opposite exterior wall. Or

alternatively, both sides can be supported by columns, which will then

make the sabat marketable to the opposite neighbor at a future

unknown time. Sometimes adjacent neighbors along the axis of the street

might also decide to build sabats. This will result in continuous

sabats abutting each other and forming a tunnel effect over the

street. The question of height clearance for the right-of-way is addressed

by Muslim jurists by stipulating that the clearance be high enough to

allow the height of a rider of a beast of burden to pass unhindered. In

certain regions the measure was a fully loaded camel. For example, in

post-Islamic Toledo, the Spanish codes of the early 15th century prescribed

that a knight with all his weapons be the measure for the clearance. One

of the stipulations in Armenopoulos's Hexabiblos (mid-14th century)

specifies that any projections, such as balconies, must allow a clearance

of 15 feet above the street level.

There are other considerations to be aware of, which are not discussed

in this essay, related to the distribution of responsibilities among various

parties whose decisions affected the built environment, the procedures

that were followed in making those decisions, and the manner conflicts

were addressed and resolved. There are numerous lessons for us to be learned

from those considerations, particularly in viewing them as precedence

and possibly models, for simplifying our procedures and patterns of responsibility

allocations that in many instances are hindrances to achieving equity

and quality in the built environment.

The following publications by Besim Hakim elaborate on various aspects

of this essay, and may be consulted for detailed information, drawings,

photos, and references:

. "Julian of Ascalon's treatise of construction and design rules from

6th-c. Palestine," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians,

Vol. 60, No. 1, March 2001, pp. 4-25.

. Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. Kegan

Paul, London, 1986. Second revised edition, 1988. ISBN 0-7103-0094-8.

. "The Role of the 'Urf' (Customs) in Shaping the Traditional Islamic

City." Journal of Architectural & Planning Research, Vol. 11, No.

2, Summer 1994, pp. 108-127.

. Sidi Bou Sa'id, Tunisia: A Study in Structure and Form. Technical

University of Nova Scotia, Halifax, Canada, 1978. Out of print but available

from Books on Demand program of University Microfilms International, Ann

Arbor, Michigan. [Order No. AU00072].

. "Islamic Architecture and Urbanism." Encyclopedia of Architecture:

Design, Engineering and Construction, Volume 3, John Wiley & Sons,

Inc., New York, 1989, pp. 86-103.

. "Rule systems: Islamic," Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture

of the World, (3 vols.), edited by Paul Oliver, Cambridge University

Press, 1997, Vol.1, pp. 566-568.

. "Urban design in traditional Islamic culture: Recycling its successes."

Cities, Vol. 8, No. 4, November 1991, pp. 274-277.

. "Reviving the Rule System: An approach for revitalizing traditional

towns in the Maghrib." Cities, Vol. 18, No. 2, April 2001, pp.

87-92.

For sources by other authors:

. Vasso Tourptsoglou-Stephanidou, "The Roman-Byzantine Building Regulations."

Saopstenja, 30-31 (1998-1999), pp. 37-63, Belgrade, 2000.

. Enrico Guidoni, La Citta Europea: Formazione e significato dal IV

all XI secolo, Milano, 1978 (also available in French and German editions).

See chapter 2: "La Citta Islamiche," pp. 54-91, which contains numerous

examples of cities formed and/or directly influenced by Islamic codes

in Spain, Sicily, and southern Italy particularly in Puglia province.

Additional information and examples by this author is available in the

chapter titled: "La Componente Urbanistica Islamica nella formazione delle

citta Italiane," pp. 575-597, in the book Gli Arabi in Italia,

Edited by F. Gabrieli and U. Scerrato, Milano, 1979.

. For studies and images in color and black & white of numerous locations

in the Mediterranean: Mediterranean Vernacular, by V.I. Atroshenko

and M. Grundy, London, 1991. And the following books by Norman F. Carver

Jr.: Greek Island Villages, Italian Hilltowns, Iberian Villages, North

African Villages, all published by Documan Press Ltd., Kalamazoo,

Michigan.

Besim S. Hakim, FIACP, AIA, has been researching and writing about

codes from the Mediterranean region since 1975, with the goal of providing

lessons and models for contemporary and future architects, urban designers,

city administrators and officials, and lawyers. He has practiced architecture

and urban design and taught those disciplines for over two decades.